Prince Hall was born around 1735, most likely enslaved. By the time he reached adulthood, freedom had been secured, but freedom came with sharp limits. Colonial America offered Black people little more than survival. Education was restricted. Political participation was nearly impossible. Professional networks were closed by design. White Freemason lodges, which functioned as social, political, and economic gateways, rejected Black applicants outright. Instead of accepting exclusion, Prince Hall pursued legitimacy.

In 1775, he and fourteen other Black men were initiated into a British military Masonic lodge stationed in Boston. That single moment would become the foundation of an entirely new tradition in Black America.

Building African Lodge No. 1

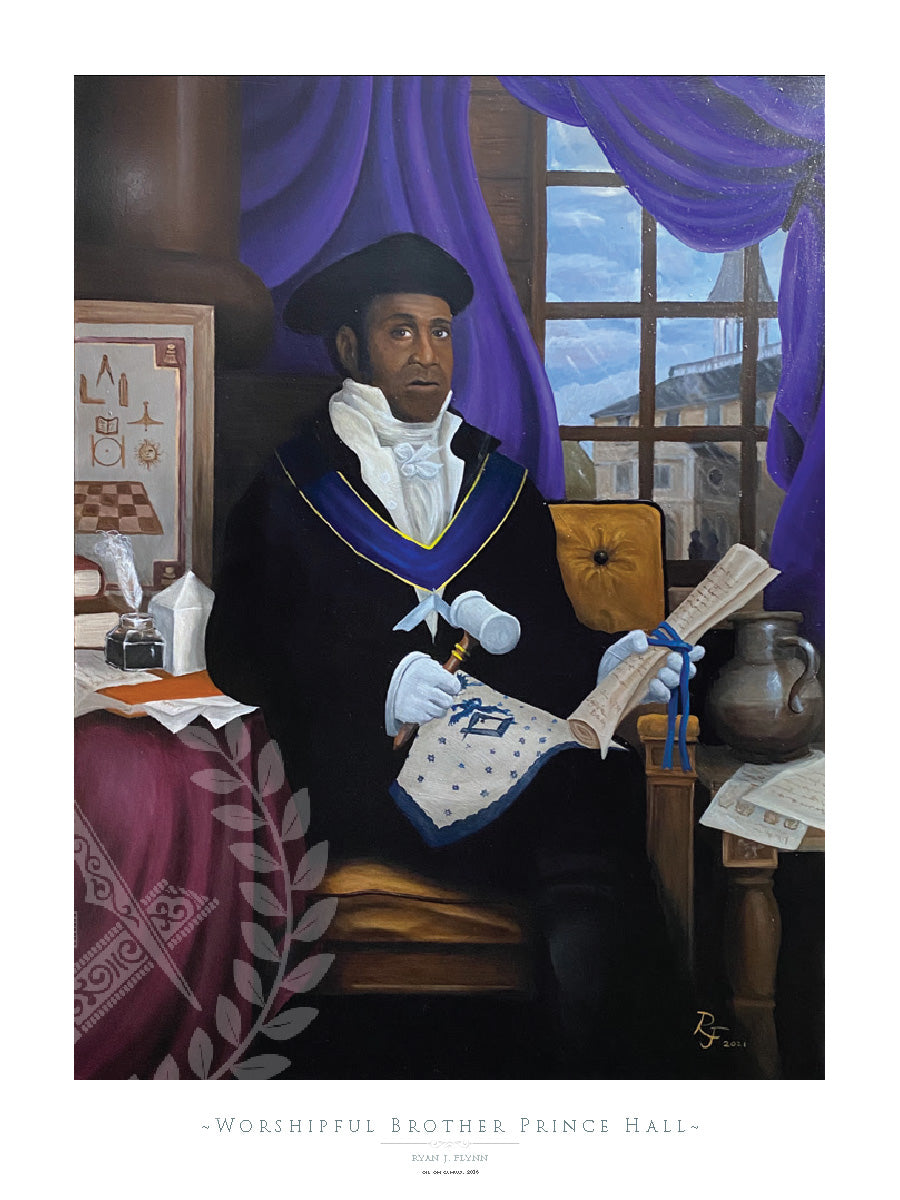

Denied recognition by white American lodges, Prince Hall sought authorization elsewhere. In 1784, he received a charter from the Grand Lodge of England, formally establishing African Lodge No. 1. This was more than symbolism.

The lodge became a center for education, leadership development, and mutual support. Members discussed politics, supported widows and orphans, organized community aid, and created a space where Black men could cultivate discipline and dignity in a society determined to deny both.

Prince Hall Masonry offered something rare at the time: collective power that could not be easily dismantled.

Faith, Freedom, and Public Voice

He petitioned for the abolition of slavery, spoke out against the kidnapping of free Black people, and argued for education as a moral and civic necessity. His writing connected Christian ethics with human rights, long before those ideas were popular—or safe—to express publicly.

Unlike many reformers of his era, Prince Hall did not wait for permission to speak. He used the lodge as a platform to organize, influence, and protect his community.

The Brotherhood That Endured

Prince Hall died in 1807, but the institution he created did not fade.

Prince Hall Freemasonry expanded across the United States, especially during periods when Black Americans were excluded from unions, professional organizations, and political spaces. Lodges produced educators, ministers, business owners, civil rights leaders, and organizers.

Historically Black fraternities, mutual aid societies, and even early civil rights structures borrowed heavily from the blueprint Prince Hall established: discipline, secrecy when necessary, service always.

Why Prince Hall Still Matters

Prince Hall Masonry is often misunderstood, misrepresented, or ignored entirely in mainstream historical narratives. That omission is not accidental.

His legacy reminds us that institutions matter. When systems refuse to include you, building your own is not separatism—it is survival. And sometimes, it is the only path forward.